Soon as I can fit you in my Disk Schedule...

Someone recently asked me a question about Lift algorithms (or Elevator algorithms for all you coders across the pond). It had been a long time since I covered them in my degree, so I had trouble giving a good answer. I don't like not knowing stuff, so I did some research and figured I'd blog up a quick outline.

Elevator Lift Algorithms are a subset of Disk Scheduling Algorithms. So we'll start there.

Disk Scheduling Algorithms are concerned with the handling of requests for reads or writes to a disk, the goal being to fairly and efficiently deal with requests that relate to many different places on a disk platter. In the case of disk reads and writes, there is a cost in handling two request in different places on disk sequentially, known as the seek time. This is the time it takes to move the disk head from one block to another.

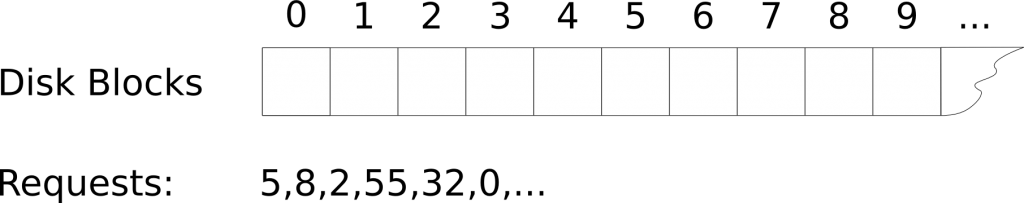

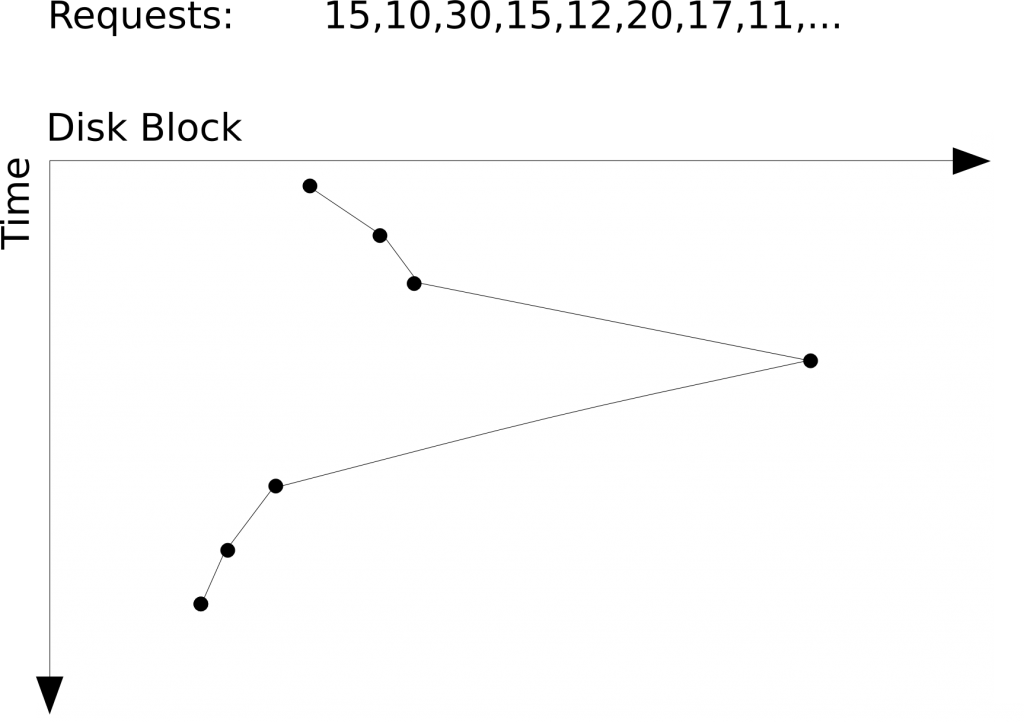

From the perspective of the algorithm, a disk is abstracted down to a 1-dimensional array of blocks. Requests are reduced to a location within that array. So the problem now looks like this:

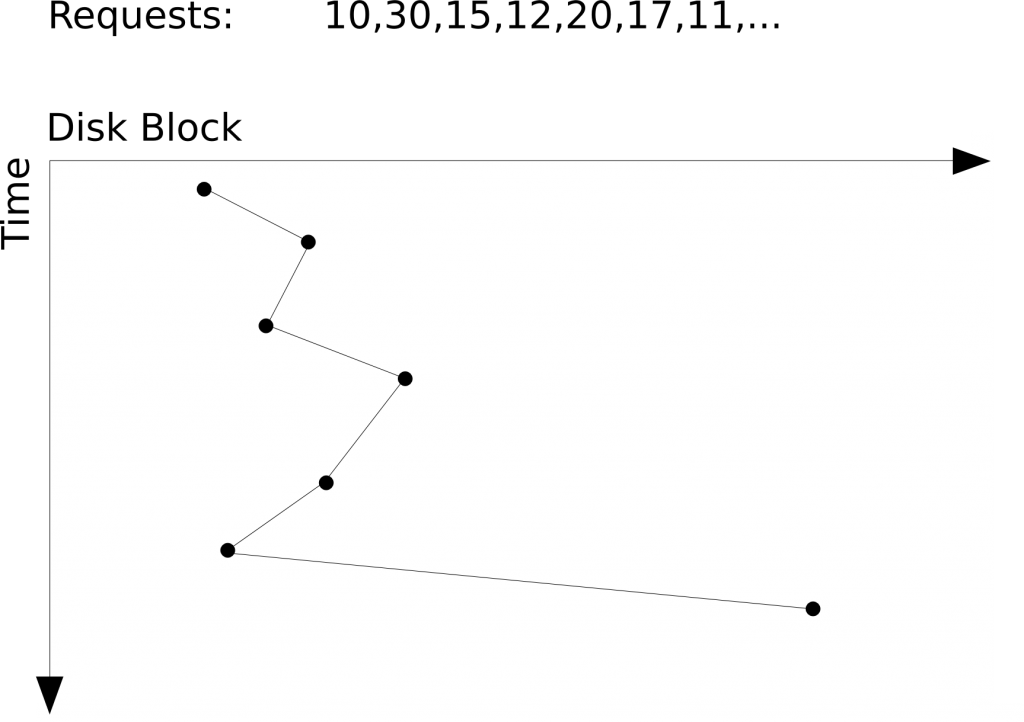

The easiest way to deal with the queue is in the order in which it arrived. This is known as First Come First Served (FCFS) scheduling. Of course, this doesn't take into account the distance between requests at all, so there is the potential for long seek times.

If we want to minimise seek time, we could try looking for the closest request in the queue to our last request. This is known as Shortest Seek Time First (SSTF). While efficient in terms of distance travelled, this algorithm can lead to some distant requests being ignored in favour of lots of closer ones - starvation.

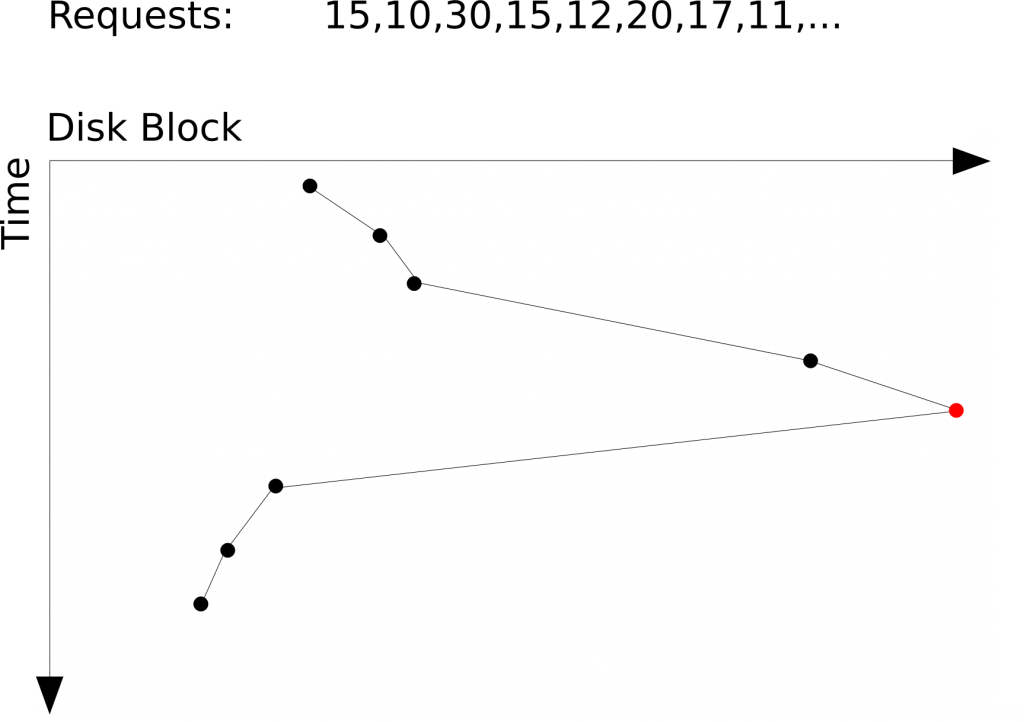

Now we come to the Uppity box algorithms. In the Lift algorithm (also known as SCAN), the head moves from one end of the disk to the other, servicing requests as it goes. When it reaches the end of the disk, it will return and services requests in the opposite direction.

This algorithm doesn't suffer from starvation as easily as SSTF, but requests for blocks in the middle of the disk will tend to have shorter wait times than those at the extreme ends.

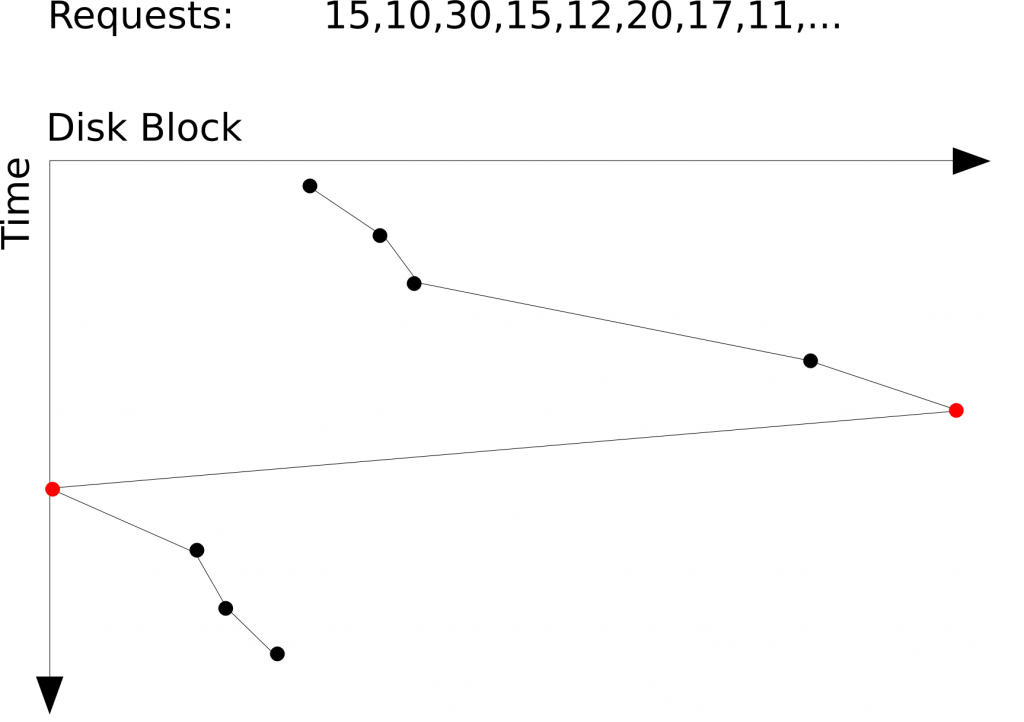

A variant is C-SCAN, which treats the disk as a circular array (hence the name). Requests are only serviced in one direction. When the end of the disk is reach, the head returns to the start and the process begins again. This has the advantage of providing a more uniform wait time than SCAN, although the overall time is greater.

Another alternative, similar to SCAN is LOOK, which will similarly move in one direction at a time, but will change direction once it has dealt with the far-most request in the queue.

C-LOOK is, unsurprisingly a circular variant of LOOK, which returns to the request with the lowest block number upon servicing the request with the highest.

So there we have it, just a basic outline, enough to remind me of what I covered at uni at least. There are a few other algorithms out there, like FSCAN and N-Step-SCAN, maybe I've inspired you to take a look. Now if I can just figure out when the heck this would be useful in Java.