iOS Shooter Designs Part 2: Anatomy of a Scene and Level Layout

This week in the iOS Shooter Project, I'm going be designing how the game scenes will fit together and how levels will be laid out. I'm going to look at scenery, what elements will interact with one another and what happens to everything that isn't on screen.

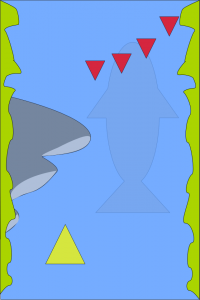

Let's start by looking at a simple scene with a few foreground, background and "in play" elements:

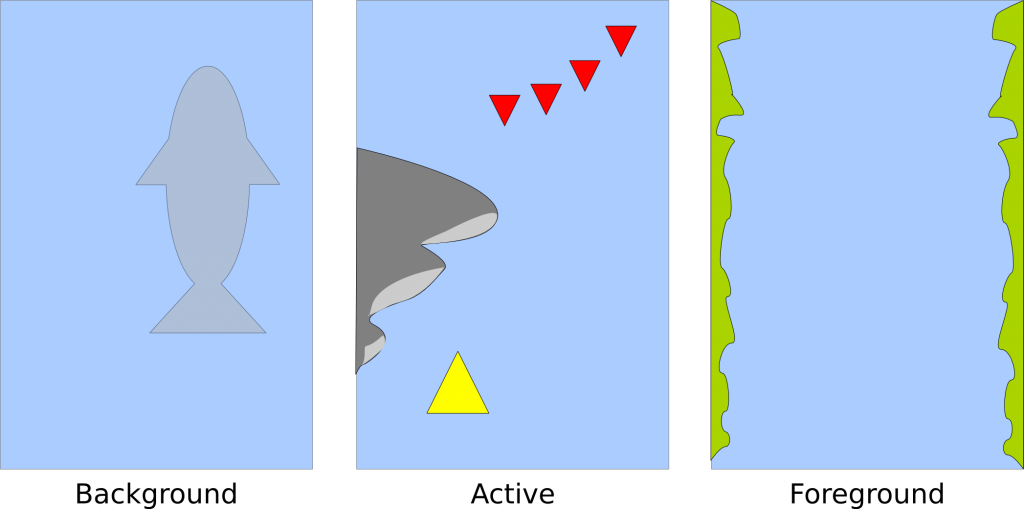

This scene consists of the Player (yellow), 4 enemies (red), an obstacle (light and dark grey to the left) as well as some foreground scenery (green) and a whale in the background. The foreground and background will not interact with the player, and will not be subject to collision detection, so we can separate the scene into three layers:

Only elements on the active layer will be able to interact with the Player and will thus be subject to collision detection. All such elements can be considered to be at the same height as the Player. Elements in the background can be considered to be below and those in the foreground can be considered to be above. The foreground layer will obscure the Active layer, so it is important that the amount of content on this layer is limited.

In order to better illustrate this vertical separation, parallax scrolling will be used. Parallax scrolling is a technique used in many scrolling games that serves to simulate the manner in which stationary objects at varying distances from our eyes appear to move when we move. Objects that are closer will appear to move more quickly than distant objects. Thus the Background will scroll more slowly than the Active layer, and the Active layer will scroll more slowly than the Foreground.

Level Layout

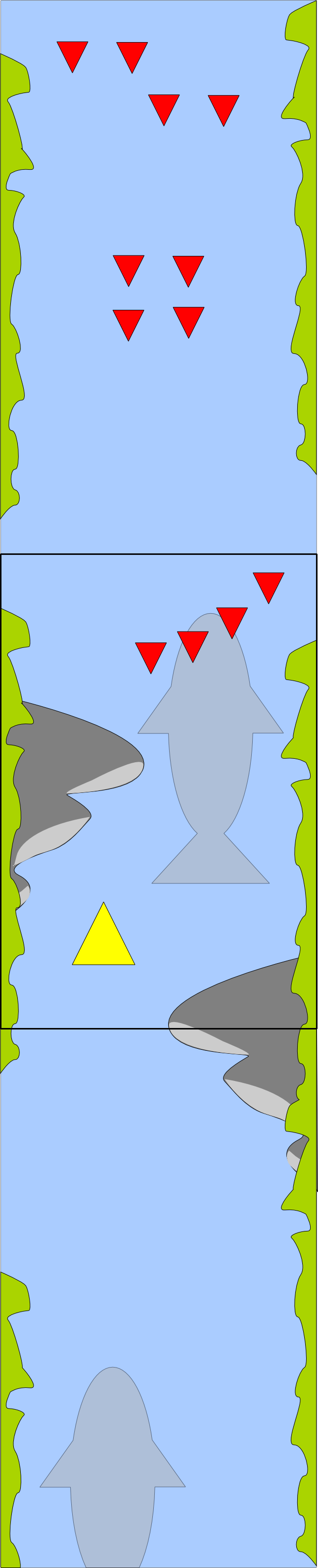

Fundamentally, a level in a top-down scroller is a long "corridor" over which the screen acts as a moving window:

Here we see the screen about halfway along this level segment, containing the player. Any effects of parallax scrolling have been ignored.

Representing a level

The whole of each level will need to be represented in memory in some manner. However, the game will only render and conduct collision detection on the segment that is visible on screen.

I had originally considered representing each level as a series of 64x64 tiles, in order to simplify laying everything out. This will work fine for the Foreground and Background layers, but I decided against this technique on the Active layer for a number of reasons. Firstly, additional logic would be required to handle active elements larger than a single tile (ensuring all relevant ). Secondly, it would limit the range of placement for each element, and prevent any overlapping (even of transparent areas) that would allow for close groupings of enemies.

So in summary, the Background and Foreground will be stored in memory as a grid of 64x64 tiles, whereas Enemies and Obstacles will be recorded with an absolute position in the level.

When Enemies Appear

The absolute position of an Enemy in a level layout would be treated as it's starting position. Each Enemy would remain in this position until they become visible on screen, at which point the Enemy would be activated and begin moving accordingly. For most cases, this model will work fine. However, in other games, certain "swarming" Enemy types would appear from the side of the screen. This would be difficult to achieve if Enemies always activated at the top of the screen.

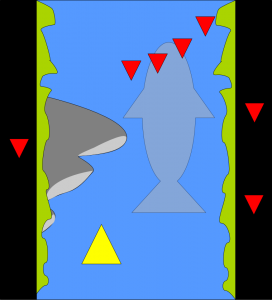

In order to allow from this, I will permit Enemies to be placed initially off-screen (with an x co-ordinate outside the main "corridor"). They will then be activated by a specific event, such as the Player passing them, or the Enemy position reaching a certain place on screen. Once activated, the Enemy would then move onto screen according to it's defined behaviour.

How to create a level

There are two possible approaches for creating the levels themselves. I could either rigidly define the structure of each level, designing them myself and bundling them as files with the game. Or alternatively, I could attempt to build levels using Procedural Generation. In this context, Procedural Generation is a technique whereby level maps are generated based on a mathematical function, their contents determined at runtime by applying this function, possibly with a seed value.

Building the levels procedurally would certainly be more interesting from a technical perspective, and once the generation function is in place, might actually save some time in the long run. However, it would require careful design and possibly a lot of tweaking to ensure an acceptable difficulty curve. Always being one for a challenge, I'm going to attempt it this way at first. However, I will design the in-memory representation of a level with a view towards being able to swap out procedural generation and replace it with the static file technique should things not work out.

Slowly but surely, we're getting there!